From the title you might be thinking that the theme of this article is something like “information security is war.” But that’s not it.

From the title you might be thinking that the theme of this article is something like “information security is war.” But that’s not it.

I recently attended a Long Island IBM i User Group (LISUG) meeting as a participant on a panel of security experts. The moderator and the audience asked questions and the three panel participants got to pontificate on the answers. I bring this up because, in the course of answering a question about what we believed was the single biggest security related issue facing IT today, I hit upon a very useful and, I believe, very accurate analogy.

My answer to the question “what is the biggest security related issue facing IT today?” was the following:

Management is not performing their rightful roles in the security management process.

What happens today in most companies is the equivalent of Army generals giving soldiers a few weapons and then telling them to figure out which battles to fight.

In other words, management is not providing the strategic leadership and decision making required by their roles in the information security management process. I firmly believe that this is by far the biggest security-related problem faced by IT shops in most companies today. Even more daunting is that the supposed generals in the information security war don’t seem to recognize this as a problem!

Who’s In Charge Here?

Let’s delve into this analogy. In an army, generals are responsible for strategic planning and accomplishing the state’s primary objectives. They determine when, where, and how best to defeat the enemy. They are also responsible for communicating this strategy, through written orders, to their direct subordinates. Each member of the general’s staff creates more detailed orders for their subordinates, and so on until orders are received by the lowest level commander in the army – second lieutenants.

Second lieutenants determine how they will use their squads (usually 12 or soldiers) to accomplish the specific tasks they have been given. For example, to reach a certain hill or town by a specific time. He or she may assign a couple of soldiers to charge up the middle, and a few to guard the unit’s rear and flanks depending on the circumstances and the objectives. Once these assignments are made, it is up to the soldiers to use their training with established processes and procedures to successfully accomplish their tasks.

Soldiers (company grade officers and enlisted men) perform specific tasks designed to help higher level field grade officers achieve their assigned objectives. General officers ensure (or are supposed to ensure) soldiers are properly equipped and trained for the battles that the commander intends them to fight. Soldiers don’t decide which battles will be fought; only how to use the training and tools they have been given to most effectively and efficiently fight the battles into which their officers lead them.

Tasks and objectives assigned to individual soldiers rarely can be used to discern an army’s overall objectives.

At the highest level, orders define strategy and objectives for the entire army. For example, “We will defeat Hitler by invading the European continent on the Normandy coast of France, gaining a beachhead, and spearheading a drive through France to Germany.”

Orders at the lowest level define tasks and the processes and procedures soldiers will use to accomplish those tasks. For example, “our company’s task is to gain control of the town of St. Mare Eglise. We will parachute into the Cotentin peninsula about 5 miles south of town. By dawn of D-Day, third platoon will secure the northern entrance into the town and prevent an enemy counterattack. First squad, third platoon will ensure that the town hall tower is clear of all enemy snipers and spotters, denying the enemy the tactical information they need to launch a counterattack. The rest of third platoon will set up a machine gun nest on all north-south roads. You can expect artillery support from ships off the coast.”

Orders often include a section entitled “Commanders Intent.” This section explains an order in more detail and provides a sort of framework that helps subordinates make decisions when the commander cannot be reached or there is no time to consult the commander.

Sans knowledge of the overall army objectives, observing the results of individual unit responsibilities won’t tell you how well you are progressing towards the army’s objectives.

The general’s strategy and objectives are fairly concrete. Once they are set, they don’t change very often. Soldiers’ tasks and the processes and procedures they use to accomplish them will change much more often depending on the nature of the task and the behavior of the enemy.

How to Set Strategy & Objectives for Information Security

Now let’s discuss how the roles in an army map to the roles in mid-sized or large businesses with respect to IT and information security. C-level executives such as the CEO, CIO (sometimes the CFO) are the general officers of the company with respect to information security. It is their responsibility to ensure that the entire management chain understands his or her strategic information security goals and responsibilities within the company. They need to have an understanding of who their adversaries are and the goals of those adversaries in order to develop a coherent strategy.

An army general doesn’t need to know how to fire a howitzer. They do need to know, at basic level, how many howitzers they need, who needs them, and how they are used in battle. Similarly, executives don’t need to know how to configure a firewall, but they had better understand what firewalls are designed to accomplish, who in their organization is responsible for them, and generally how they are used to combat attackers.

Corporate Instructions

For information security, executive orders must be in the form of written, high-level strategies and objectives. In the business world, these may be in the form of a corporate instruction. For example, “No employee should be capable of accessing business information that is not required to accomplish the tasks and objectives associated with their job.” These instructions may include the equivalent of the commander’s intent section of an army order. For example, “The word ‘capable’ in this instruction means that employees are prevented from accessing business information that is not required to perform their job duties.” Depending on the company and the nature of the business, there may be just a handful of corporate instructions in some way related to information security, or there may be more.

The direct subordinates of the CEO represent the army’s field grade officers. They may be C-level executives, general managers, division heads, or directors. It is the responsibility of all of these subordinates of the CEO – not just the CIO – to ensure corporate instructions are translated into appropriate information security policies for their organizations.

Security Policies

Security policy describes the behaviors and actions of people that need to be ensured, prevented, or detected in order to meet the objectives and intent of corporate instructions. This means the CFO needs to ensure that the data owned by his or her organization has been properly categorized and high level behaviors, with respect to financial information, have been properly defined. The same is true for the Director of Facilities and every organizational entity that reports to the CEO.

Security policies represent the mid-level battle plan for achieving the intent of corporate instructions. Some policies may need to be broken down into more specific policies. This may be required for individual departments to be able to translate security policies into the specific technical tasks, processes, and procedures they will use to accomplish their technical tasks.

Applying Security Policies

Employees are responsible for understanding policies and how they inform their individual behaviors. Some of these behaviors will be intuitive. Some will need to be defined in terms of processes and procedures that must be used to perform certain tasks. An example of a procedure for producing the end-of-month financials might be something like, “To ensure no financial information can be inadvertently compromised, you may print reports only when you are able to immediately retrieve them.” Department managers, team leaders, and employees may all participate in generating written processes and procedures.

Information security is not the sole responsibility of the IT shop! The procedure described in the paragraph above is a good example of a security policy that is not implemented or enforced by the IT shop.

Of course, the IT shop will have many more processes and procedures for enforcing information security than most other organizations in the company by virtue of the fact that it owns the equipment – and the operation thereof – that processes and stores the data. For example, they need to create and manage userIDs. There should be corresponding written process and procedure for how this task will be accomplished. Developing a written process or procedure starts with ensuring that all of the security policies related in some way to the process are understood. A security policy might say “An employee’s manager must approve the creation of a userID.” Another might say “only employees in the finance department can be authorized to run the finance applications.” And yet another might say “only employees approved by management on an individual basis are allowed to access financial data by means other than approved financial applications.” A written process for creating userIDs must incorporate the ability to enforce, prevent, or detect these behaviors.

Ideally, the process will describe in some detail what information is to be provided to the system administrator and by whom. It should also describe how the system administrator uses this information to make specific technical decisions about which userIDs to create and how they should be configured.

“Good” Security Requires Engaged Generals

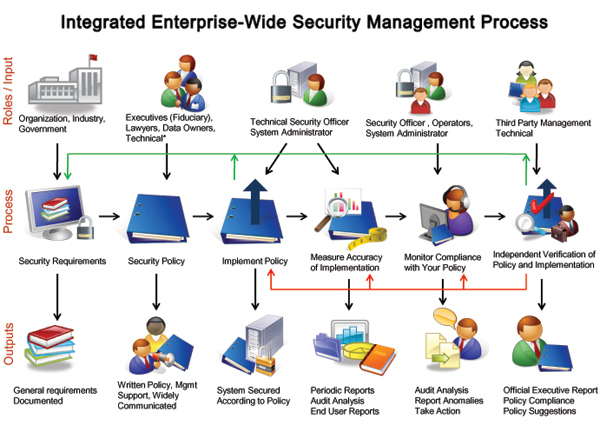

As you can see from the discussion above, information security management is first and foremost a critical business process. That business process begins at the highest level of the organization, but every level and every part of the organization needs to be involved. Click here to see a full-sized picture describing this process. The bottom line is with a flawed or nonexistent security management process, you’ll get a flawed or unmeasurable level of security.

As you can see from the discussion above, information security management is first and foremost a critical business process. That business process begins at the highest level of the organization, but every level and every part of the organization needs to be involved. Click here to see a full-sized picture describing this process. The bottom line is with a flawed or nonexistent security management process, you’ll get a flawed or unmeasurable level of security.

Now let’s go back to my answer to this question: “what is the biggest security related issue facing IT today?” I said:

Management is not performing their rightful roles in the security management process. What happens today in most companies is the equivalent of Army generals giving soldiers a few weapons and then telling them to figure out which battles to fight.

The problem starts at the top. CEOs are not nearly as involved as they need to be in defining corporate strategies and objectives. They have nearly abdicated their role in information security to the CIO. Without a clear understanding and communication of the strategic information security objectives it is not possible to develop the security policies required to achieve those objectives. Without security policies, employees in or out of the IT shop can’t possibly understand their role in protecting information, or what behaviors are required in order to protect information.

Instead, we give employees anti-virus programs, firewalls, intrusion detection software, etc. We might even tell them to avoid downloading software from external web sites. Then we tell them “to do their thing and protect that data!” We don’t define what needs to be protected, the threats against the data, and we don’t define the behaviors necessary to mitigate those threats. Then we ask an external auditing company to come in and tell us if we are “secure.” It almost makes you laugh…almost.

In my opinion, it is no wonder we are seeing the high level of successful attacks that are occurring today. The generals aren’t aware that it’s ultimately their battle to fight. The enemy have defined the battlefield, chosen the ground they want to fight on, dictate the nature of the battle, and the soldiers are merely reacting to the fight that is brought to them. They’re winning many of the battles, but they can’t hope to win the war.